A Nation of Gradgrinds

I had a good day. I had lunch with a fellow academic I didn't know really well, and it turned out perfectly. This restored my faith in my social skills (I am a very nice, friendly person, perfectly capable of forming friendships and having sparkling conversation--as long as it's not with a group of half-drunk lawyers that turns into a vortex of vapidity), my faith in humanity (people are nice, intelligent, funny), my faith in the human intellect (we are capable of learning beyond our chosen disciplines). Yes, you can talk about everything from critical theory to the academic market to law to music to baseball to behavioral evolution to disability rights to Sean Penn's acting skills in less than 2 hours! Go ahead, give it a whirl!

I came home, vacuumed, read, took my arthritic mother for a walk, watched Star Trek, read some more.

And then at 9 pm, my 14 year old nephew gives me a call. Can I please help him with his essay?

I became an aunt at 11 years old. A child, loving another child. I don't have "favorites," (blah blah, not supposed to) but I do have a special bond with this child. Up until two years ago, he would hold my hand as we walked together, telling me that he loved me. Just two years later, he's a few inches taller than me, has this suspicious light black matter on his upper lip, and refuses to say anything other than "te amo" (because if it's in Spanish, it's not as embarassing when I demand "Tell me you love me!" (I am going to be a fun mother). So I have love for the boy.

But the boy can't write to save his life.

He is an otherwise smart boy, but he lacks inquisitiveness, attention to detail, imagination, and a logical mind. I say this with love, but with desperation. Because I saw this in the faces of some of the students I have taught in my very short life and academic career. He reminds me of the college students I TA'd who would ask "tell me what to write." Or worse yet, the students who ask "tell me what to think." You get a few of these students every year. I don't want the boy to turn into one.

Granted, the boy is only 14. But I can imagine him becoming one of those college juniors (not transfer, not recent immigrant, not ESL) students I've TA'd who cannot write a grammatically correct sentence. This worries me. He is pretty good at science and math, I'll grant. But is it always either/or? I used to think I really sucked at math, but it's mostly laziness and my lack of desire to study for subjects I'm not very interested in. Bad trait, I know. But I'm hoping it's this bad trait rather than a total lack of comprehension and ability in explaining the boy's writing difficulties.

I didn't speak English until I was 5 years old, when I entered kindergarten, at which point I lost most of my native Vietnamese and never looked back. I never really struggled, and never even took ESL (which is why I'm offended when people presume that every foreign looking kid had to, and can only understand you if you SPEAK REALLY LOUD). I went to relatively OK public schools, but mostly, I just learned how to write by reading a lot. I was a precocious child reading David Copperfield at 10, Madame Bovary at 11, and am reverting to the "fun" books I missed at this age. This boy spoke English by 3, when we enrolled him in preschool and then pre-K. He went to a good, expensive private school until just last year. And still, the boy's writing skills appear to be worse than an ESL student. His grammar appears to show no improvement, and his ideas are tautological, obvious, or nonsensical. Oftentimes, I wonder how he reaches his conclusion. It will be A, B, and then Thus, C. Huh?

I spent two hours on the phone with him tonight, going over each line of a two page essay. I showed him his grammar errrors, and things that just did not make sense. I pointed out that street fights are fought between the servants of the two families, not by the servants of the two families; that it was the parents' treatment of Romeo and Juliet that contributed to their deaths, not their personalities; that "When Mercutio and Tybalt are dead because of another street fight, the Capulets, saying that Romeo is the cause of this, stood up for Tybalt, and the Montagues, saying that Romeo justifies Mercutio’s death by slaying Tybalt, stood up for Romeo" is not a proper sentence; and....oh, brother, you get the idea. What's worse, I hate this play. It is pure treacle compared to Shakespeare's superior historical plays. One catch to having kids is that you have to relive every indignity of youth, like being forced to read crap like "The Pearl" or "The Good Earth." How do my grad school friends handle this? How can they stand reading crappy essays about putrid books day in and day out? True, college students are better than any high school student (particularly freshman)--but I've TA'd 7 college classes--it's not always that much better. Sometimes, you want to pierce your eyes out for having been made to witness the murder of a language or work of literature you love. I weep for my corneas.

Yet, I can't blame the boy entirely . He tries hard, and asks me for help well in advance of the due date--believe it or not, what he sends me is usually his second draft. I have told him to read a 30 page writing handbook I have compiled for him. I have told him to read his sentences out loud to see if they make sense. I have told him to diagramm his essays to make sure the ideas connect (like dots) and logically lead to his intended conclusion. I have told him to pay attention to the details so that he doesn't write "when a street fights break out." The boy's problem is not laziness (although I think his frustration with his difficulty with the subject impedes his effort and learning, just as it did mine with calculus), but rather being too narrowly focused. He doesn't read for the love of reading--he does what he is told. He doesn't set out to write clear arguments persuasively--he writes to the rules. He pays so much attention to the rules that he'll cram two sentences in one to meet the sentence limit for a paragraph. He pays such close attention to the word limit per paragraph, that he goes after numbers rather than clarity. So I say to you, Mrs. ___ and School District _____, what the fuck are you teaching my child?!

These are the rules he has to write by:

Outline for a Five (or more) Paragraph Essay:

Essay

Structure:

The first paragraph, the introdution, should contain the following in

two to three sentences.

Paragraph #1:

Hook

Thesis

Identification of Author and Source (If Necessary)

The following three (or more) paragraphs are body paragraphs. They should support the said thesis in Paragraph 1.

Paragraph #2 - 4 (Or more):

Sentence 1 should be a topics sentence explaining what the paragraph is going to be about.

Sentence 2 should be a detail from the source supporting the idea of the topic sentence.

Sentences 3 - 4 should both be a commentary about the detail in Sentence 2. Both should not be detail.

Sentence 5 is the same as Sentence 2.

Sentences 6 - 7 is the same as Sentences 3 - 4.

Sentence 8 should be the conclusion of theat paragraph or a transition to the next.

This is the last paragraph of the essay. Must contain two to three sentences.

Paragraph 5 (A higher number if written written with more than three body paragraphs):

1: It should state why the three body paragraphs support the thesis in one sentence.

2: It should restate the thesis in different words.

These are district wide rules, people! I don't know if they'll change next year (and I pray, by junior/senior year), but the boy has to write a thesis paragraph in THREE sentences and around 50 words. I have no idea what these exacting rules (the violation of which will result in loss of points) are supposed to accomplish. Maybe to ruin the English language and prevent the communication of ideas, thereby ensuring the destruction of the world. Paranoid? You think? What other explanation for these draconian requirements that teach kids to write to the rules rather than write to convey an idea? It's like teaching to the test--where is the search for truth and understanding in all the rote memorization?

What will become of our civilization if our children do not learn anything of significance or insight in all their 12 years of education? What will become of them if they leave school knowing only rules and facts rather than knowledge and wisdom? Presuming that the motivation is utility, efficiency, and clarity, what do these draconian requirements achieve but to bury our children's imaginations and inquisitiveness under the depressing weight of conformity to rules, rules, rules?!

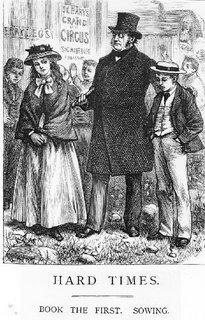

Are we to become a nation of Gradgrinds?

There were five young Gradgrinds, and they were models every one. They had been lectured at, from their tenderest years; coursed, like little hares. Almost as soon as they could run alone, they had been made to run to the lecture-room. The first object with which they had an association, or of which they had a remembrance, was a large black board with a dry Ogre chalking ghastly white figures on it.

Not that they knew, by name or nature, anything about an Ogre. Fact forbid! I only use the word to express a monster in a lecturing castle, with Heaven knows how many heads manipulated into one, taking childhood captive, and dragging it into gloomy statistical dens by the hair.

Louisa:‘Would you have doomed me, at any time, to the frost and blight that have hardened and spoiled me? Would you have robbed me — for no one’s enrichment — only for the greater desolation of this world — of the immaterial part of my life, the spring and summer of my belief, my refuge from what is sordid and bad in the real things around me, my school in which I should have learned to be more humble and more trusting with them, and to hope in my little sphere to make them better?’

‘Yet, father, if I had been stone blind; if I had groped my way by my sense of touch, and had been free, while I knew the shapes and surfaces of things, to exercise my fancy somewhat, in regard to them; I should have been a million times wiser, happier, more loving, more contented, more innocent and human in all good respects, than I am with the eyes I have. Now, hear what I have come to say.’

‘With a hunger and thirst upon me, father, which have never been for a moment appeased; with an ardent impulse towards some region where rules, and figures, and definitions were not quite absolute; I have grown up, battling every inch of my way.’

‘I never knew you were unhappy, my child.’‘

Father, I always knew it. In this strife I have almost repulsed and crushed my better angel into a demon. What I have learned has left me doubting, misbelieving, despising, regretting, what I have not learned; and my dismal resource has been to think that life would soon go by, and that nothing in it could be worth the pain and trouble of a contest.’

<< Home