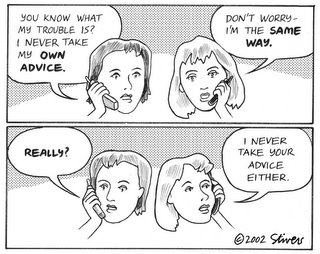

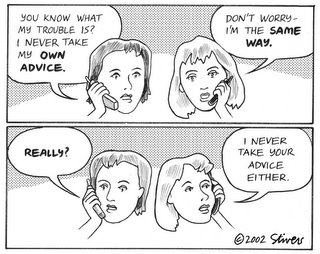

I should begin with an admission: I'm not a huge fan of Richard Delgado. I used to feel very conflicted about this (and

some of you know I'm always conflicted and overwhelmed with existential guilt), because he's one of the "founding fathers" of Critical Race Theory. So when I say I'm not a fan of Richard Delgado, I feel like I'm just adding one more stab of betrayal at CRT. But you know, enough self-flagellation. I've made my apologies to CRT, andI may one day find my way back to it. But I'm actually not sorry at all that I don't like Delgado's work. I'm done with it.

As a terminally-conflicted person, I am usually most conflicted between my populist values and my elitist tendencies. On the one hand, I grew up poor, where even Doritos were a luxury. We slowly got into the middle class as each kid graduated thanks to federal grants and got well-paid jobs, supporting each other through school and paying into this mutual family fund that supports our parents. I thus have an appreciation for all things middle--middle class and middle brow. On the other hand, I'm well educated in the liberal arts, and so I have a definite hierarchical, canonical thinking mind. I won't say "Applebees is the root of all base, American gluttony"--if you like Applebees, and if it's a treat for you and your family the way McDonalds was for mine when I was child, good for you. Treat your family, and enjoy being together no matter where you go to celebrate that Student of the Month award. At some point, my family outgrew McDonalds (we now go to fancier chain restaurants to celebrate things), but we still try to keep things we do as a family more about the family and less about where we go. So I'm not one of those people that says when you're all excited about where you're going to go to celebrate that 3 month anniversary "oh, that restaurant wasn't highly Zagat-rated. I wouldn't go there." Why rain on someone's parade? If you're excited to go, go. I think negative comments can be kept afterwards, and each experience (and palate) is entirely subjective. I rarely ever inform someone of my plans in order to get a rating. I hate it when people say "Oh I've been there, done that, didn't think much of it, but go ahead, go and see if it works for you." That said, I'm not so forgiving when it comes to literature, film, art, and scholarship.

Just as I would bitch-slap someone for saying that Oprah's Book Club obstacle-triumphalizing treacle is as good as say, the lyrical brutality of any book by Ian McEwan or J.M. Coetzee (not to mention Nathaniel West), I would highly question any scholar who thinks that (prolific as he is) Richard Delgado is the best representative of CRT out there. I think the best work has been done, and is being done, by Derrick Bell, Devon Carbado, Cheryl Harris, Angela P. Harris, and Charles Lawrence. Between theorizing about the legal construction of race, (e)racing the 4th Amendment, whiteness as a property value, critical race feminism and unconscious racism-- these are the superstars of the CRT movement. I read these articles and wanted to go to law school and study CRT. I still love reading these articles. They're just amazing pieces of scholarship. They may begin with a personal narrative contextualizing the project, but the actual article itself is just solid legal scholarship. This is another weird conflict of mine--I'm as post-modern deconstructivist as the next lefty academic, but I generally like to keep my own narrative voice distinct from my analysis. In other words, I can inject enough of myself into my work to make sure the reader is aware of my perspective, but I make sure to let that normative narrative voice go when I do the analysis. This has nothing to do with whether I believe in objectivity or identity politics--it's just I like to keep my voices separate and clear. There's preface voice, and then there's the actual article that is supposed to be drawing from more than personal experience or perspective to make its arguments. It's like the book jacket/acknowledgements part of the book, where you learn of the author's journey in writing the book about these Nazi camp survivors, who turn out to be her grandparents, versus the actual narrative voice of the book, which may be omnicient, a third-party, or one of the grandparents themselvs.

Richard Delgado doesn't really like my separate narrativity argument. He likes to confuse things. He writes entire articles in a narrative fashion, writing in the voice of a fictional academic talking to a fictional student. Here's the book jacket blurb: "Delgado (law, U. of Colorado) creates a challenging dialogue between two African-Americans (a brilliant law student and a disheartened legal scholar and activist) whose conversations traverse critical race theory, the black left, the rise of the black right, feminism, and the economics of racial discrimination. "

I can't stand these pieces. For one thing, the professor comes off as a pretentious blowhard, chuckling at his own professorial cleverness, clucking his tongue as he tries to guide his brilliant young protege. Plus, for all the anti-discrimination theorizing Delgado does, he comes off as remarkably elitist and patronizing--these are just two dudes having Grand Conversations about Big Important Things in a cushy teacher's office over pizza. I know they talk over pizza. Delgado writes that in as a part of a scene, I suppose to add some verisimilitude. (I for one have never had pizza in a professor's office, they never seem to have anything to offer)

I can't stand this work! I can't believe it was published in the major law reviews in the country! You don't believe me? Here's the intro to the

first of

six Rodrigo Chronicles:

"Excuse me, Professor, I'm Rodrigo Crenshaw. I believe we have an appointment."Startled, I put down the book I was reading [ and glanced quickly first at my visitor, then at my desk calendar. The tall, rangy man standing in my doorway was of indeterminate age-somewhere between twenty and forty-and, for that matter, ethnicity. His tightly curled hair and olive complexion suggested that he might be African American. But he could also be Latino, perhaps Mexican, Puerto Rican, or any one of the many Central American nationalities that have been applying in larger numbers to my law school in recent years."Come in," I said. "I think I remember a message from you, but I seem not to have entered it into my appointment book. Please excuse all this confusion," I added, pointing to the pile of papers and boxes that had littered my office floor since my recent move. I wondered: Was he an undergraduate seeking admission? A faculty candidate of color like the many who seek my advice about entering academia? I searched my memory without success."Please sit down," I said. "What can I do for you?"

(turns out Rodrigo is an Italian student seeking to enter an LLM program and the American academic market)

From the section entitled "In Which Rodrigo Begins to Seem a Little Demented" (I am not making that up):

But now, as you can see"-Rodrigo gestured in the direction of the window and the murky airoutside-"Saxon-Teuton culture has arrived at a terminus, demonstrating its own absurdity."*

"But let's suppose for the sake of argument that you have made a prima facie case, at least with respect to our economic problems and to issues concerning race and the underclass. I suppose you have a theory on how we got into this predicament?""I do," Rodrigo said with that combination of brashness and modesty that I find so charming in the young. "As I mentioned a moment ago, it has to do with linear thought-the hallmark of the West. When developed, it conferred a great initial advantage. Because of it, the culture was able to spawn, early on, classical physics, which, with the aid of a few borrowings here and there, like gunpowder from the Chinese, quickly enabled it to develop impressive armies. And, because it was basically a ruthless, restless culture, it quickly dominated others that lay in its path. It eradicated ones that resisted, enslaved others, and removed the Indians, all in the name of progress. It opened up and mined new territories-here and elsewhere-as soon as they became available and extracted all the available mineral wealth so rapidly that fossil fuels and other mineral goods are now running out, as you and your colleagues have pointed out."

"Rodrigo, you greatly underestimate the dominant culture. Some of them may be derivative and warlike, as you say. Others are not; they are creative and humane. And even the ones you impeach have a kind of dogged ingenuity for which you do not give them credit. They have the staying and adaptive powers to remain on top. For example, when linear physics reached a dead end, as you pointed out, they developed relativity physics. When formalism expired, at least some of them developed Critical Legal Studies, reaching back and drawing on existing strands of thought such as psychoanalysis, phenomenology, Marxism, and philosophy of science." What about the exploitive capacity of the colonizing conquistadors? Wasn't the rise of commercial city-states in Renaissance Italy a central foundation for subsequent European cultural imperialism? Most ideas of Eurocentric superiority date to the Renaissance and draw on its rationalist, humanist intellectual, and artistic traditions.""We've had our lapses," Rodrigo conceded. "But theirs are far worse and more systematic."

"What about Rembrandt, Mozart, Shakespeare, Milton? And American popular culture-is it not the envy of the rest of the world? What's more, even if some of our Saxon brothers and sisters are doggedly linear, or, as you put it, exploitive of nature and warlike-surely you cannot believe that their behavior is biologically based-that there is something genetic that prevents them from doing anything except invent and manufacture weapons?" Rodrigo's earnest and shrewd retelling of history had intrigued me, although, to be honest, I was alarmed. Was he an Italian Louis Farrakhan? "The Saxons do all that, plus dig up the earth to extract minerals that are sent to factories that darken the skies, until everything runs out and we find ourselves in the situation where we are now." Then, after a pause: "Why do you so strongly resist a biological explanation, Professor? Their own scientists are happy toconjure up and apply them to us. But from one point of view, it is they whoseexploits-or rather lack of them-need explaining."

These are not even the best examples of Delgado's patronizing tone (wow, how did Radical Rodgrigo get so good at online research, such that he surpasses the Professor? How could he have learned that in Italy? Wow, is Radical Rodrigo racially ambiguous!) , nor his effluvia of highly dramatized personal observations about Radical Rodrigo. The Professor is constantly alarmed, charmed, taken aback by, and amused by his young protege. Oh, and at least he concedes that his Saxon brothers and sisters are capable of producing more than linear derivative thought and warfare. But can you read much more of this?

I was forced to read it in CRT, where I first learned to hate Delgado. I hate the Chronicles, I hate his tendency to over-cite himself, I hate his heavily redacted, simplistic CRT "coursebooks." Much better are books by Derrick Bell, Juan Peres, Kimberle Crenshaw. I just can't say it enough. Delgado sucks. If you ask other current CRT scholars privately, they'll say that they hate his books and dislike the Rodrigo Chronicles too. Problem is, he is one of the "founding fathers" of CRT (although THE Godfather is Derrick Bell), so it's hard to come out and say it. So as a young, brash, aspiring scholar after Delgado's own heart, I'll be brave enough to come out and say it. I'd say it under my own name too, if I thought there was any point to it. It's not that I think Delgado does particularly shoddy scholarship. I just hate his use of narrativity in the Rodrigo chronicles. His "plea for narrativity" I dislike for other reasons (mainly, how to avoid identity politics and extra-legal, personal anecdote in one's legal analysis), but I think it's an argument for inclusion made in good faith, and I won't hate him for that. No, I just hate his patronizing, condescending, elitist, egocentric narrative tone that he seems to employ in

everything.He uses it in his "advice column" for aspiring academics and academics of color at one of my favorite blogs,

BlackProf. It's not always bad advice (usually, I agree with the basic conclusion)--I just can't stand the tone in which it is written:

From "

Sex in the Stacks:

Javier (fictitious name, real person) writes that he is falling in love with his research assistant, Hermione, a top law student and member of the law review. Javier, who received tenure after a divided vote last year, is afraid that some of his colleagues who voted against him in the tenure decision will come out of the woodwork if he acts on his impulses with the beauteous and smart Hermione, and try to get him, this time for good.

So far, Javier and Hermione have kept their relationship within bounds. But the other evening, after the two of them worked until late in the night in Javier’s office, editing his law review article, Javier drove Hermione home. The moon was full, their hearts beat as one, they exchanged meaningful looks—and Hermone dashed out of the car door mumbling, “Oh, Javier, sweet Javier, what are we to do?”

Javier fears that the next time they are together, they will know what to do, and will do it. She is 25, he 31. Both are single. What are they, indeed, to do?

MOM SAYS that Javier and Hermione must run, not walk, to the faculty manual, which is probably on the university’s website if not gathering dust on Javier’s shelf, and use their highly developed research skills to find out the university’s position on amorous relationships between students and faculty. That position will almost certainly look askance at romantic relationships between professors and students who are currently taking their courses or under their wing as, for example, research assistants.

First of all, do you think "Hermione" would say "Sweet, sweet, Javier" (and how on earth did he pick this name combo?)

From "

A Bird in the Hand"

Dear Mom. I have offers from two law schools and must reply by next week. One, from regional school A, would enable me to teach in the city where I currently live. This would greatly please my wife, who is a medical resident at the local university, and two children, both of whom are in school and would hate to move. The other offer is from school B, which is over 600 miles away and would force me into a commuter relationship with my family. School B is higher ranked than school A and has better research support. But if I took the job at school A, I would have more opportunities to write, since I wouldn’t be commuting all the time, and might be able to move to a better school after a few years and a few law review articles.What should I do?

Dear Julian. Mom thinks that you are right to be perplexed. You stand at a genuine crossroad. If you take the offer from school B, your family life may suffer and your children may come to hate you. Your wife may take up with a dashing young surgeon and you will spend cold nights alone in City B, wishing that you had stayed home and tended to first things.

On the other hand, if you accept the offer from school A, you may find yourself weighed down with a high teaching load and the myriad of committee responsibilities that regional schools seem to impose on young scholars. You may have more time to write but find that that time goes to endless busywork and conferences with students who didn’t get it the first time. If your plan to write your way onto a better faculty doesn’t work out, you may spend the rest of your career at School A, pining for the toney shores of School B that you gave up in a rash, youthful decision.

Wow, the choices seem really draconian. Your wife may leave you, and your children may come to hate you. Or, you'll suffer neverending regret and dissatisfaction over a "rash, youthful decision." Sucks to be you!

I can't stand this anymore. I think I need to stop reading Delgado, period for a while. Maybe this is contributing to my frustration with CRT at present, although reviewing all the good CRT authors I've read makes me feel a little nolstalgic for "the way it could be." But the problem in any scholarly movment is that there are the good apples, and there are the overly-fragranced, dyed-red, noxiously sweet and cloying apples. The genetic frankenfood in the bin that seems too fabricated and waxy to be appealing. As much as I support CRT's anti-discrimination project and its theorizing about race, I just can't stand behind conflicting, counter-productive uses of narrativity anymore.

I need to find my own voice, I can't be bothered trying to separate a dozen in one article.